Understanding China's Rise in a Globalising World, 2023: Foreign Policy Memos

This page features some of the best student foreign policy memos about UK-China relations written in Spring 2023.

The University of Manchester is committed to academic independence and the freedom of speech. Student views are entirely their own, and do not represent those of the University of Manchester, MCI, or UCIL.

UK foreign policy memos

Addressed to UK Foreign Secretary James Cleverly.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Adam Sharpe

Date: 16 March 2023

Re: Chinese Involvement in Infrastructure Projects

Executive Summary

Relations with China and attitudes towards Chinese investment ought to be reconsidered in an effort to further British progress with large infrastructure projects.

This includes transport projects such as the HS2 and more sensitive areas, namely the UK’s 5G network and nuclear power sector which could be aided by Chinese investment and technology.

Background

Numerous infrastructure ventures have faced delays or cost related issues which has meant the UK fell behind other nations in staying up to date with technological advancements. Chinese investment has been inconsistent with Brexit uncertainty and Covid induced economic slowdowns. However, interest existed before as over £105bn was allocated in 2014 for UK recipients in energy, property and transport (Plimmer, 2014). The Chinese sovereign wealth fund sought beneficiaries for investment which the UK could offer with projects such as the HS2 and cellular networks improvements.

The UK is yet to make use of the Chinese BRI scheme, which funds infrastructure, due to insecurity in UK-China relations but the BRI has been effective and has led to projects completed sooner and cheaper (Korablin, 2019). Exploring alternative financing options of works on this scale could benefit the UK.

The present policy is Chinese investment is welcome, except in industries deemed as strategic which encompasses nuclear power and the 5G network. New policy should alter this position and make decisions in the best interests of the British public (Parker and Thomas, 2021).

Policy Options

Open up to Chinese investment in all sectors:

UK infrastructure could benefit from Chinese investment in areas currently restricting investment, notably 5G and the nuclear industry. The existing 5G system which relies on Huawei technology is set to be stripped of this equipment by 2027 (MoD, 2021) and this would not be an effective decision if the aim is to improve telecommunications throughout the UK.

Decisions should reflect governmental aspirations instead of copying sanctions imposed by the US, thus reversal of this policy to have an effective 5G network sooner should take precedence. Furthermore the removal of Chinese firms from all nuclear power projects could be reversed, this policy was only implemented over fears of military applications to nuclear technology.

However, if Chinese ownership was capped to around 10% or involvement was solely tied to investment, then this could be a viable revenue source for UK nuclear development. Potential setbacks to opening up to such investment could include straining the US-UK special relationship as the attitudes towards China’s role in infrastructure would be contradictory, but this level of fallout seems unlikely given the deep alliance that exists.

In addition, there have been concerns about national security being hindered by Chinese interference, concerns mainly raised by the US and Australia. Therefore, a UK review into these accusations could be useful to have more information before making conclusions and implementing policy which could have significant impacts on the global scene.

Encourage wider non-sensitive investment:

Chinese interest in investing in UK transport and property markets is already present and could be allowed to take place on a wider scale. This would assist in not only the financial side of these industries but also timescales of project completion, most predominantly of the HS2 railway connecting London to the North. The UK could even go beyond this to set up other new rail infrastructure or port developments as have been prevalent across Europe with Chinese state backing.

There is a risk of cutting off British investment into the UK itself as several industries become more greatly funded by Chinese businesses, however that is the nature of upholding an open economy. Whether this would be interpreted as a negative impact depends on the opinions of the public.

Additionally, dependency on Chinese funding for crucial industries could become an issue as US-China decoupling becomes more common whilst economic self-sufficiency takes centre stage for those countries. This would mean that there is a reliance on the continued success of China’s economy which could be a high-risk strategy considering the current fragile state of global politics.

UK funded Chinese infrastructure building:

An alternative view would be that the management and breadth of these projects is the issue rather than investment itself. Thus by allowing the government to fund the projects, ownership could be maintained while Chinese companies are employed to carry them out.

This would negate any security concerns and if utilising the BRI, the UK could borrow money from China to complete the project and as a developed nation, should not face the issues of debt that countries in Africa and Latin America have experienced (Liu et al, 2020).

A downside would be that by taking full UK ownership, this is a more expensive policy route to choose as a precautionary measure when concerns about security may not be true. Other BRI projects have had issues beyond sinking economies into debt, overall quality of the works have been questioned but whether more qualified oversight would counteract this is unknown (Dube & Steinhauser, 2023).

Policy Recommendation

Allowing investment in all sectors with proper project oversight and limits on Chinese involvement should be the new policy choice for UK-China investment relations. This is preferable to current policy of completely cutting off potential investment in areas deemed sensitive, because these large scale infrastructure projects are direly needed for the UK to stay among the forefront of the global economies.

Through adopting this policy, the nuclear sector could begin to flourish and there would be a greater self-sufficiency of energy, highlighted as an issue with the dependence on gas and non-renewable sources. Additionally, a widespread 5G network would ensure greater capacity and reliability of telecommunications which could allow new digital industries and businesses to grow with a UK hub.

Lastly, Chinese investment to complete the HS2 would limit delays on the already late scheme and finally build the increasingly expensive transport system which has been proposed for over a decade at lower cost. Becoming a destination for Chinese direct investment could greatly help the UK not fall behind other G7 nations in terms of economic growth. It would also aid China as they seek safe destinations for their capital and would find this in the UK, where investment has slowed but confidence is returning.

Sources

- Dube, R. and Steinhauser, G. (2023). China’s Global Mega-Projects Are Falling Apart. WSJ

- Korablin, S. (2019). China: investment ambitions, limitations and opportunities. Economy and forecasting, 2019(3), pp.106–121. doi

- Liu, Z., Schindler, S. and Liu, W. (2020). Demystifying Chinese overseas investment in infrastructure: Port development, the Belt and Road Initiative and regional development. Journal of Transport Geography, 87, p.102812. doi

- Ministry of Defence (MoD). (2021). Project Delivery Functional Strategy. Retrieved from GOV.UK website.

- Parker, G. and Thomas, D. (2021) UK says China is welcome to invest in non-strategic parts of economy. FT.com

- Plimmer, G. (2014) China set to invest pound(s)105bn in UK infrastructure by 2025. FT.com.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Charles Kane

Date: 20 March 2023

Re: Hong Kong Emigration Cost Assistance Proposals

Summary

China - UK relations have changed and morphed over the past 20 years. The recent events in Hong Kong have shaped a path for soft powered British intervention, specifically through the creation of simpler migration pathways for Hong Kong nationals, as was attempted in July of 2020.

Since then, only 150,000 have emigrated over (Lee, 2023), out of the possible 5.4 million potential applicants (Wade and Gower, 2021).

Emigrating to the United Kingdom is a very costly process, and this policy recommendation letter will highlight some of the ways in which the British state can assist more Hong Kong nationals financially to emigrate over to the United Kingdom, namely through assistance with: accommodation, travel, and legal costs.

Accommodating much of Hong Kong's population in a fashion like this could put pressure on the government of China to treat the citizens with the legal respect specified in the 1997 Sino-British joint declaration (Brooke-Holland, 2019), developing Sino-British relations in a manner that reflects British ethical expectations.

Background

In July 2020, the British government, then led by Boris Johnson, announced new safe immigration pathways, allowing select Hong Kong nationals to move and reside in the UK, with a route to eventual citizenship. This policy is significant because it is applicable to so many, and it also demonstrates the United Kingdom's soft power capabilities in the face of China’s authoritarian governance.

However, whilst this policy has potential to significantly impact the CCP and provide safety for Hong Kong's resident’s, it has caveats, particularly regarding finances. The pathway from Hong Kong national to British citizen will cost each person at least £6965 (British National Overseas visa, 2023), disregarding -the already expensive- accommodation and transport.

This is an outrageous sum that ensures freedom only for those who can afford it. A new policy should be introduced, creating a fund for those who need extra financial assistance, thus improving the UK’s tarnished record on compassion for asylum seekers (Rawlinson and Thomas, 2020).

By pressuring the Chinese government into rethinking their treatment of Hong Kong citizens, a new path for Chinese-British relations can be created, one that more closely resembles the golden age of relations experienced between our two nations. In doing so we can mutually aim to prosper economically, socially, and environmentally.

Analysis of policy options

There are several ways in which the British government can financially aid those living in Hong Kong, this letter will address three of the most effective strategies. As stated, the following bullet points explain interventions regarding accommodation, transport, and legal costs.

One way the British government can assist those Hong Kong nationals seeking a new life in the United Kingdom is through providing short or long term accommodation options for those who need it. One advantage of this policy is that it would tackle the most expensive aspect of emigrating to Britain, as UK house prices have risen considerably over the past decade (Office for National Statistics, 2022). However, in turn, this would also prove to be a very expensive policy, and it would need to succeed alongside the other, already overcrowded, asylum seeker accommodation options.

Additionally, assistance from our state can be given to those making the journey between the UK and HK through helping them with their travel costs, partially or fully. This is important as HK nationals may not have the funds to immediately travel to the UK due to cost, some flights are well in excess of £1000 (British Airways, 2023).

This is especially important for those who need to leave for safety concerns. One issue with such a policy is that an uptick in flights may make it more difficult to facilitate all of those that wish to emigrate, however schemes that assess urgency, can be introduced in order to tackle this issue by creating lists of priority.

One of the easier solutions to confront the costs is to directly lower the legal prices Hong Kong nationals will face, this has actually already been done through the creation of the BNO visa, which is considerably cheaper than other visas (Walsh, 2020). However there are other areas where the costs stack up, namely the “Immigration health surcharge” (£3120), indefinite right to remain (£2389), and the registration as a British citizen (£1206).

One advantage of cutting these costs is the simplicity of the task. It is very easy for the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development office to apply changes to these costs, and is probably the most efficient way to assist HK citizens. One disadvantage is that the results from this are not immediate, for instance, unlike subsidised transport costs, a HK citizen would not immediately benefit from having a cheaper application to become a British Citizen.

By utilising any one or all of these policy suggestions, the likelihood for a citizen to make the move to Britain will increase, moreover, those utilising the suggested policies may represent some of the poorer within Hong Kong, and by extension, the most powerless. And so it can be argued that such policies will benefit those who need help the most, ensuring that any Hong Kong national can seek freedom regardless of their financial wellbeing.

These policy options would put pressure on the Chinese government to respect the individual rights of Hong Kong citizens, as a population loss also represents an economic loss, especially in one of the most financially developed regions in the country.

References:

- British Airways, (2023). British Airways, Travel. [Website displaying ticket prices]. [Accessed 21st March 22]

- British National (Overseas) visa. (2023). Commonwealth citizens and British nationals (overseas). [Accessed 21st March 22]

- Lee, P. (2023). Over 144,000 Hongkongers move to UK in 2 years since launch of BNO visa scheme. Hong Kong Free Press. 1st February. Online

- Office for National Statistics. (2022). Home Economy Inflation and price indices UK House Price Index, London. His Majesty's Land Registry.

- Rawlinson, K. Thomas, T. (2020). UK government accused of lacking compassion for asylum seekers. The Guardian. 2nd September. Online

- Wade, E. Glower, M. (2021). Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa. [Online]

- Walsh, P. (2020). Q&A: The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa. [Accessed 20th March 23]

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Conor Glynn

Date: 19 March 2023

Re: Muslims in Xinjiang

Summary

I propose a boycott of products containing cotton from the Xinjiang region and significant trade restrictions on Chinese industries utilising products from Xinjiang and a public awareness scheme of the atrocities occurring.

Background

Human rights violations are ongoing in Xinjiang, China, with over 1 million Uyghur Muslims detained since 2017 (House of Commons, 2021), subjected to forced labour and re-education camps to erase Uyghur culture.

There’s an estimated over 380 of these camps (Council on Foreign Relations, 2022) despite claims from the CCP that they had been shut down in 2019. The UN describes this situation as constituting “crimes against humanity” (United Nations, 2022).

This represents a serious issue for the UK. With the UK’s global outreach, condemnation is needed. The cotton industry is a huge issue as the Xinjiang region is currently responsible for over 85% of Chinese cotton output (Li, 2021), amid evidence of forced labour by Uyghurs.

Current UK policy isn’t enough to force change. There’s been a review of export controls to Xinjiang and guidance for UK businesses setting up links to Xinjiang (Bunkall, 2021), coupled with asset freezes for 4 Chinese government officials (Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office, 2021).

This isn’t enough without economic threat. Following refusal from the UK government to ban imports of Xinjiang cotton (AP News, 2023), we aren’t taking a strong enough stance.

Policy options

I propose several policies to address the Xinjiang problem:

- The UK and Chinese governments must engage in consistent dialogue, raising concerns about Xinjiang. Moreover, the UK must place pressure by supporting for Chinese human rights activists to force the CCP’s hand. This policy won’t directly cost the UK and could lead to greater cooperation between the 2 countries over future issues.

However, this policy could compromise future deals and discussions. Credible threats need to be made to China which could place future discussions in jeopardy. Dialogue alone simply isn’t enough:

- Multinational corporations play a huge role in the sustained growth of the Chinese economy, with MNCs previously responsible for over half of Chinese exports (Woetzel et al., no date). At least 83 multinational companies (Yang and Shepherd, 2020) are current beneficiaries of forced Uyghur labour. The UK government must place pressure on companies, particularly British MNCs, to withdraw from the Chinese market until aforementioned issues are addressed. It’s unlikely change occurs if threats are made without economic costs to China. Withdrawing huge amounts of investment by MNCs represents a significant threat. Following the Better Cotton Initiative raising awareness of forced Uyghur labour in products, companies such as Nike, Adidas and H&M announced a boycott of Xinjiang cotton (Jin, 2022). This highlights the importance of awareness schemes. The UK government must encourage similar action from British companies benefitting from Xinjiang.

However, complex global supply chains provide difficulty in identifying what companies benefit from Xinjiang. This policy will be costly to the UK government- significant incentives must be provided to withdraw from the Chinese market.

Outsourcing cotton production away from cheap labour in China is difficult to encourage companies to do, never mind the loss of global supply links this entails.

Support from the UK government has encouraged companies to do this, excluding suppliers linked to human rights violations (Bunkall, 2021). Nevertheless, more can be done:

- The UK government could work with allies, placing global economic pressure on China to address Xinjiang. Economic sanctions can be placed, boycotting Xinjiang cotton, limiting cooperation with the government and trade deals conditional on human rights improvements. The US represents China’s largest export partner, with exports worth $45.4 billion (OEC, no date) in 2022 along with huge amounts to the EU. Trade restrictions will cause a huge dent to the Chinese economy, forcing change. This policy encourages dialogue between the UK and its allies, proving beneficial in future.

However, it’s troublesome to find a united consensus on the policies that should be used. Furthermore, whilst the West represents a big market for Chinese trade, large amounts of trade happen in Asia. ASEAN was China’s second largest trading partner in 2022 (Statista, 2023).

Decoupling from the West, leaning more towards the Asian and Russian market, has already begun in China. It’s unlikely that these sanctions may have the desired effect, instead pushing China further towards ASEAN and Russia without change in Xinjiang. This could further fracture the global economy, causing economic downturn in the UK.

Policy Recommendation

Thus, I recommend a boycott of Chinese products containing Xinjiang cotton, coupled with trade restrictions (deals conditional on human rights improvements) and a public awareness scheme. China relies on international trade- it’s the number 1 & 2 exporter and importer in the world respectively (OEC, no date), therefore sanctions based on trade will force change.

Public awareness campaigns implore UK citizens to learn about Xinjiang, encouraging conscious consumption decisions regarding goods from China. Boycotting Xinjiang cotton sends a message to China, reinforcing the UK’s role as a global standard setter of human rights.

A message that the UK won’t stand for human rights violations must be sent for change to occur, which current policy measures aren't doing. Economic deterrent is the best way to do this. Dialogue with the CCP isn’t enough; credible threats must be present. The above policy represents these threats, endorsing change.

This isn’t to say that this policy won’t be costly or induce retaliatory measures from the Chinese government. This will be costly regarding UK trade- China is currently the UK’s fourth largest trading partner (Lawrence and Myers, 2023). The UK relies heavily on China for imports, with a trade deficit of £40.5 billion (The Institute of Export and International trade, 2022).

Arguably, this weakens our standings on human rights issues- we benefit from the Chinese economy, which has grown by these. The UK committing to economic boycotts and sanctions might not be enough. The UK is only China’s 9th biggest trading partner (Workman, no date), thus may not be enough of a deterrent for change.

It’s important the UK is a global standard bearer for human rights. We must be willing to deal with potential consequences of its policies. Whilst it may seem a pointless endeavour to announce trade restrictions due to the size of the UK market, this may lead to similar actions from allies, providing economic threat for China.

The UK can only look introspectively, it cannot act conditional on other countries. We must set the standard. Consequently, the UK must implement the policy discussed above. The UK cannot stand for human rights violations.

Sources:

- AP News (2023) UK judge rejects Uyghur bid to halt Xinjiang cotton imports, AP News (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Bunkall, A. (2021) Uighur Muslims: New measures by UK to tackle China ‘human rights violations’, Sky News. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Council on Foreign Relations (2022) China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, Council on Foreign Relations. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office (2021) UK sanctions perpetrators of gross human rights violations in Xinjiang, alongside EU, Canada and US, GOV.UK. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- House of Commons (2021) The UK’s responsibility to act on atrocities in Xinjiang. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Jin, W. (2022) ‘Nike’s Relation with Non-government-organizations’, in. 2021 International Conference on Public Art and Human Development ( ICPAHD 2021), Atlantis Press, pp. 1132–1135. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Lawrence, F. and Myers, A. (2023) ‘Trade and Investment Factsheet’. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Li, X. (2021) Western crackdown inspires Xinjiang cotton industry to rise - Global Times. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- OEC (no date) China (CHN) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners | OEC, OEC - The Observatory of Economic Complexity. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Statista (2023) China: main export partners based on export value 2022, Statista. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- The Institute of Export and International trade (2022) The Institute of Export and International Trade, The Institute of Export and International Trade. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- United Nations (2022) China responsible for ‘serious human rights violations’ in Xinjiang province: UN human rights report | UN News. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Woetzel, J., Ngai, J. and Seong, J. (no date) The new challenges for MNCs in China | McKinsey. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Workman, D. (no date) China’s Top Trading Partners 2021 (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

- Yang, Y. and Shepherd, C. (2020) ‘Xinjiang forced labour reported in multinational supply chains’, Financial Times, 1 March. (Accessed: 19 March 2023).

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Coralie Roads

Date: 14 March 2023

Re: Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang

Summary

There is increasing evidence that the cotton fields of Xinjiang, China are using forced labour of Uyghur Muslims from ‘re-education centres’ (Xu et al, 2020). It is believed to be the largest-scale detention of religious minorities since World War Two (Lehr and Bechrakis, 2019).

To address this problem, the UK government should introduce sanctions and restrictions on companies importing cotton from Xinnjiang or using forced Uyghur labour. This is an opportunity to impose strict inspections on labour conditions in the global supply chain and apply pressure on the Chinese government to put an end to forced labour.

Background

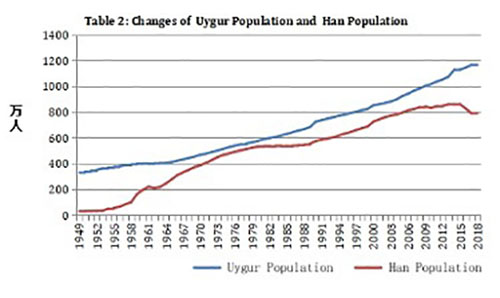

Xinjiang lies in the north-west of China and is home to around 12 million Uyghur Muslims. Uyghurs in this region have faced discrimination at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as their attempt to secure control over the population (Stern, 2021). This oppression has escalated to “crimes against humanity and genocide” since 2014 with reports from NGOs, such as Amnesty International, of a mass detainment of Uyghurs in ‘re-education centres’ (Stern, 2021, p1).

An estimated one million Uyghurs have been arbitrarily detained against their will, where they have been subject to various forms of torture, such as forced cultural assimilation and political indoctrination (Amnesty International, 2021). The detainees are unable to leave or communicate with family outside the re-education centres. The Chinese government state that this crackdown in Xinjiang is necessary to prevent terrorism and the re-education centre root out Islamist extremism (BBC, 2022). This re-education has the aim of strengthening loyalty to the Communist party.

There is increasing concern that the Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang ‘re-education centres’ are involved in forced labour. Xinjiang produces around a fifth of the world’s cotton and there are concerns that much of this cotton is picked by forced labour. There is evidence that new cotton factories have been built within the grounds of the re-education centres (BBC, 2022). This is part of the Chinese government’s efforts to eliminate the Uyghur culture by re-educating them through a different style of work (Lehr and Bechrakis, 2019).

The situation is Xinjiang involves the use of “compelled labour as part of a concerted effort [from the Chinese government] to eliminate a culture and religion” (Lehr and Bechrakis, 2019, p2). The UK government are morally obligated to enact a new policy to address this issue to uphold human rights standards across the global stage.

Policy options

China has attracted international condemnation for its use of forced labour and ‘re-education’ camps in Xinjiang in the past decade. In March of 2021, the European Union sanctioned China over the human rights abuses of Uyghurs. This criticism stemmed from western and northern European countries that place liberalism and human rights at the heart of their political agenda. There is evidence to suggest that this frustrated China and therefore, Beijing responded with an escalated set of sanctions against European politicians.

Western European criticism of the Chinese government proved to escalate the situation rather than address the issue. China formed new trade relationships with Eastern European countries, such as the ‘16+1’ mechanism in 2013. This sanction, in the form of direct condemnation of China, did not improve the treatment of Uyghurs but it did increase international awareness of the human rights abuses.

The UK parliament approached this issue in 2022. Rishi Sunak declared that the apparent “Golden-era of UK-China relations is over” (The Times, 2022). Referring to the mistreatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, Sunak claimed that as China has moved towards even “greater authoritarianism” under Xi Jinping , it now presents a “systematic challenge” to the UK (BBC, 2022). China’s acts against human rights go against the UK’s liberal stance.

In his bid for No 10 in July 2022, Sunak pledged to a policy to kick the CCP out of UK universities, including closing all Confucius Institutes in the UK in an attempt to intimidate China. However, China have continued to deny all allegations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

China’s foreign ministry spokesperson told the BBC in 2022 that the documents were an example of ‘anti-China voices’ trying to degrade China. This policy has not enacted change for the Uyghurs but it does send a message to the international community that human rights abuses will not be tolerated.

The Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act of 2022 requires firms importing goods from Xinjiang into the USA to provide evidence that they are not produced using forced labour. This policy addresses the compelled labour that Uyghurs face and attempts to stop companies supporting the industry. However, this policy has not ended the use of forced labour in Xinjiang. Further, many Chinese argue that the USA should not be criticising Chinese slave labour given their history in slavery.

Policy Recommendation

In a democracy, the purpose of politics is to protect individual rights. There is an opportunity for the UK to implement a new policy to approach this issue. The UK government should impose sanctions and restrictions on companies who import cotton from Xinjiang that are found guilty of using Uyghur workers in their factories.

This should include inspections determining how labour is deployed. If the company is found to be using forced labour, the UK government should apply pressure to introduce proper labour practices. Defined by the UN international convention, genocide is the intent to destroy a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group (Kunz, 1949). It is vital that through this process the rights of the Uyghurs are prioritised and their genocide is ceased.

Forced labour in Xinjiang is connected to Western supply chains. According to the International Labour Organisation, forced labour includes work that takes place under threat of a penalty and where the person has not offered their service voluntarily (Hughes, 2005).

The forced coercion of Uyghur Muslims in the global supply chain violates this international law. For example, evidence suggests that Uyghurs work in the factories of global brands such as Nike and Apple (Xu et al, 2020). There is a connection of forced labour in Xinjiang and the UK market, creating both a moral imperative for action and an opportunity to apply pressure on the Chinese government (Lehr and Bechrakis, 2019).

The coerced labour force in Xinjiang produces over 80% of China’s cotton. A report in 2020 revealed that 16% of the UK’s textile imports were from China. The aim of this policy would be for China to stop using forced labour in its markets, protecting Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang and preventing these abuses from re-occurring in the future.

Sources:

- Amnesty International (2021). The nightmare of Uyghur families separated by repression.

- BBC News (2022). Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide, 24 May, p. 1.

- Hughes, S. (2005). ‘The international labour organisation’, New Political Economy, 10(3), pp.413-425.

- Kunz, J.L. (1949). ‘The United Nations Convention on Genocide’, American Journal of International Law, 43(4), pp.738-746.

- Lehr, A. and Bechrakis, M. (2019). ‘Connecting the dots in Xinjiang: forced labour, forced assimilation, and Western supply chains’, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, pp. 1-38.

- Stern, J. (2021). ‘Genocide in China: Uighur Re-education Camps and International Response’, Immigration and Human Rights Law Review, 3(1), p.2.

- The Times and The Sunday Times (2022). Rishi Sunak: Golden era of UK-China relations is over [YouTube]. (Accessed: 14 March 2023).

- United States Customs and Border Protection. (2022). Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act.

- World Bank. (2020). United Kingdom textiles and clothing imports by country 2020. World Integrated Trade Solution.

- Xu, V.X., Cave, D., Leibold, J., Munro, K., and Ruser, N. (2020). ‘Uyghurs for sale: ‘Re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 26, pp. 3-41.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Daniel Woo

Date: 21 March 2023

Re: UK-China Trade Imbalance

Summary

The growing trade imbalance that the UK has with China will deteriorate the UK economy and its footing with China. It contributes to the lack of employment and increases unethical labour use overseas. Accordingly, we recommend that the UK government implement the supply-side policy that focuses on increasing labour skills and productivity to encourage less reliance on China’s goods and economic growth.

Background

As reported in 2021, United Kingdom’s largest trade imbalance is with China resulting in a 39 Billion Pounds deficit, it has been a significant increase of more than double the amount since 2019 which is -14 Billion Pounds and it is steadily increasing (Matty, 2022).

United Kingdom’s increasing reliance on China’s products will put them at a standpoint with no leverage, leading to a loss of influence in major decision-making relating to China.

Additionally, increasing imports from China can incur an ethical cost from labour exploitation, which was evident in the forced labour exploitation of Uyghur workers in Qingdao. There will also be a rise in the unemployment rate in the UK caused by the lack of domestic manufacturing as a result of the increase in imports.

In order to ensure that these alarming consequences from the trade deficit are prevented, there is a range of policies that could be implemented by the government.

Policy options:

1. Impose trade tariffs on China’s imports

Implementing tariffs on China’s goods does lead to a decrease in the trade deficit. In theory, it also allows an increase in the demand for local goods along with the employment rate as the price of imported goods increases opening up more job vacancies in local manufacturing. However, imposing tariffs on China’s goods will damage the China-UK relationship which can lead to a trade war, this can be seen evident during the Trump administration when the president implemented tariffs on China products causing China to retaliate and leading to a massive trade war which increased the prices for American consumers. Tariffs would also limit the products available for consumers in the UK which may result in shortages, this will further increase the prices of goods causing inflation in the long run.

2. Devaluation policy

Devaluing British Pounds can reduce the trade imbalance against China as it increases the competitiveness for exports. Foreign countries would want to import goods from the UK as it is now cheaper since the currency has weakened, and imports into the UK would also be more expensive making consumers spend more on domestic businesses. In the past, China has devalued its currency which raised its competitiveness in the global market substantially and dominated global trade. However, devaluation does not always work well as illustrated in 2011 when the Brazilian Real was devalued leading to many problems such as declining commodity prices and corruption. Another downside of devaluing foreign currency includes inflation due to the rise in the gross domestic product (GDP) of the economy driving up the demands of consumers, some local manufacturers would also have to increase their prices as the materials that are imported becomes more expensive. Locals who are travelling or working abroad would also face hardship as there will be a reduction in purchasing power overseas. Energy cost such as gas in the UK is based on the US dollar, so devaluing the Pound will lead to higher energy cost.

3. Deflationary Policies

This policy can be implemented by tightening the fiscal or monetary policy of the UK, both methods lead to the same aim of reducing aggregate demands in the UK and reducing inflation. Deflating fiscal policy reduces aggregate demand by lowering government spending or increasing taxes, this reduces consumers’ income in the UK and reduces their demand for foreign goods, increase in taxes will also improve government finances. However, with lower aggregate demand, unemployment increases which leads to the same problem as a trade deficit. Deflating monetary policy reduces aggregate demand by increasing the interest rates which increases the cost of debt and reduces consumer spending. Deflationary policies force the local manufacturer to find alternative ways to lower the cost of production in order to increase demand which makes local goods more competitive, although this method is uncertain as it depends heavily on the situation of the economy.

Policy Recommendation

In order to tackle the rising trade imbalance problem from China, we would recommend the UK government to implement the supply side policy.

The supply-side policy promotes competitive growth for UK exports and less reliance on foreign imports by improving labour productivity and skill in the economy. The measures that the government could take to achieve this include:

- Providing incentive taxes such as lowering income and corporation tax to encourage new businesses and increase employment.

- Providing better quality of education and training by increasing government spending on education and training, prioritizing the electronics sector.

- Increasing government investment in transport, which helps improve UK exports.

The effects of this method will take a longer time, but although the UK-China trade deficit is growing, it is not too severe to the point where it requires immediate action. Electronics are the main imports from China in the UK worth $28.86 Billion in 2022 (tradingeconomics.com, 2023), allocating government spending to focus on this sector will allow an increase in the production of electronic goods in the UK decreasing the reliance on China.

With high tensions currently affecting China and the West with the intent of decoupling, the supply-side policy is a more peaceful approach rather than implementing tariffs which increase tensions. This policy would also promote economic growth and would not cause consumer setbacks like devaluing and deflationary policies do, although it might widen income inequality due to sector prioritization.

Sources:

- CFI Team (2022). Devaluation. Corporate Finance Institute.

- Economics Online (2020). Supply-side policy. Economics Online.

- Jones, L. (2022). Falling pound: What does it mean for me and my finances? BBC News. 26 Sep.

- Matty, M. (2022). UK-China Post-Brexit Trade Relations. British Chamber of Commerce in China | Beijing. [Accessed 10 Mar. 2023].

- Scott, R.E. (2019). U.S. Trade Deficits: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Implications. Economic Policy Institute.

- Tejvan Pettinger (2017). Policies to reduce a current account deficit | Economics Help. Economicshelp.org.

- Thiagarajah, J. (2018). Pros and cons of currency devaluation. Daily News.

- tradingeconomics.com. (2023). United Kingdom imports from China - 1993-2020 Data | 2021 Forecast

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Edward Gum

Date: 21 March 2023

Re: Addressing the UK-China Trade Imbalance

Summary

This foreign policy memo analyses the UK-China trade imbalance whilst discussing policy options, such as tax credits and tariffs. The recommended policy is infrastructure improvement to increase the UK’s economic potential by promoting domestic production, international trade, import diversification and reduced dependency on Chinese imports.

Background

Trade imbalances occur when imports exceed exports; this has long been exhibited in UK-China trade. In 2021, China was the UK’s largest import partner and sixth largest export partner for goods, contributing 13.3% and 5.8% respectively (Donnarumma, 2022). In 2021, the trade deficit with China increased threefold due to reduced exports (34%) and increased imports (38%) throughout the Covid-19 pandemic characterised by ‘lockdown spending sprees’ thus increasing demand for Chinese goods.

The year ended with a deficit of £39.1 billion (Barns-Graham, 2022) and stood at £40.1 billion in 2022 (Lawrence and Myers, 2023). 2022 exhibited the worst UK current account deficit figure since the data was first published, 8.3% of GDP (ONS, 2022), suggesting new policies are needed. Since China contributes substantially to UK trade, a policy to address the UK-China trade imbalance seems appropriate.

Whilst not ‘inherently entirely good or bad’ (Hayes, 2022), sizable and persistent trade imbalances negatively impact a country by signally economic instability, deterring investment and limiting growth. This economic environment may reduce labour demand, increase unemployment and exacerbate the deterioration in living standards amid the cost of living crisis (Hourston, 2022).

Further concerns relate to Brexit and the subsequent deterioration in relations with the European market contributing to worry that the UK is “becoming heavily dependent on China” (Barns-Graham, 2022). Concerns are, therefore, growing contributing to uncertainty over the effectiveness of current policies.

Policy options

Policy 1 involves promoting UK exports through tax credits allowing the tapping in of ‘unrealised growth’ (Barnett, 2022). The European Commission (2010) find that European SMEs that trade internationally grow more than twice as fast as those which do not suggesting export promotion can stimulate the economy. Exporting firms benefit from economies of scale, productivity improvements and innovation allowing ‘new and improved products or services’ (Department for BIS, 2011).

Harris and Li (2007) find a ‘34% long-run increase in TFP in the year of entry’ suggesting this policy improves efficiency and economic growth. However, with substantial public sector net debt, 98.9% of GDP in 2023 (ONS, 2023), a policy reducing government revenue may be irresponsible suggesting alternative policies may be preferable. Conversely, since this policy promotes long-term growth through accessing international markets, the revenue loss may be justifiable.

However, many businesses may fail to possess the skill-sets and knowledge required for international trade, e.g. digital literacy and access to relevant contacts, suggesting a need to provide support services (Downes et al., 2018) with tax credits to maximise effectiveness.

Policy 2 involves improving UK infrastructure to enhance trade efficiency, increase market access and lower costs thus promoting export growth and boosting ‘economic potential’ (Msulwa, 2021). By lowering production costs, exports become more competitive and demand can increase. UK exports are significantly restricted by the efficiency and speed of ‘transhipment’ in airports, taking up to four hours per airside compared to 45 minutes in Dubai (Mace, 2022), illustrating the need improved UK competitiveness.

Pisu et al. (2015) further state that the UK has ‘spent less on infrastructure compared to other OECD countries over the past three decades’ meaning this policy, whilst costly, may be necessary and due. This policy, notably, provides jobs during construction of the project and the effect of this is significant with construction employing 8% of the UK population.

Improving UK infrastructure also allows those with appropriate skill-sets to ‘increase the talent pool’ (Reynolds, 2022) and access job opportunities through ‘new housing development’ or ‘strong public transport links’ promoting productivity and attracting investment for domestic industries (Horsman, 2020). The policy thus enhances domestic production and international trade, reducing UK reliance on Chinese imports by improving own production and diversifying imports, therefore, aiding in reducing the trade imbalance.

Policy 3 involves imposing tariffs on imports from China. This can reduce the competitiveness of Chinese goods by increasing prices meaning domestic goods will be relatively less expensive. Tariffs thus support domestic businesses and deter imports, both contributing to reducing the trade imbalance. However, data from 151 countries over a period of 51 years reveal tariff increases are ‘associated with an economically and statistically sizeable and persistent decline in output growth’ whilst increasing unemployment and inequality, therefore, reducing social welfare.

Labour productivity, already an issue for the UK, is found to decline by 0.9% after 5 years (Furceri et al., 2020) and the effect of this is greater for advanced economies (Furceri et al., 2018). It is estimated that the remaining US tariffs against China will reduce long-run GDP by 0.22% and wages by 0.14% (York, 2022) whilst Furceri et al. (2018) find tariffs do not improve trade balances due to appreciation, i-[‘reducing the competitiveness of UK exports, brought about by a tariff increase. Politically, tariffs may also lead to a deterioration in relations and invoke retaliation that imposes costs on the UK.

Policy Recommendation

The policy recommendation is policy 2. Whilst significantly more expensive than other policy options, the benefits are widespread, sustainable and help reduce the UK-China trade imbalance by promoting domestic production, exports and reduced reliance on Chinese imports. The policy benefits both the UK, allowing wealth to spread across the nation (Reynolds, 2022), and other countries through improved efficiency and international trade.

Bivens (2017) states this policy is useful for ‘macroeconomic stabilisation’ with the ‘output multiplier’ significantly higher than other ‘fiscal interventions’. $100 billion spending on infrastructure boosts job growth by roughly 1 million full-time equivalents meaning policy makers should avoid ‘short-termist thinking’, despite prevailing economic conditions. This policy enables modernisation and improved connectivity, necessary due to the ‘desperate need of increased capacity’, overcrowding and aging infrastructure (Reynolds, 2022).

The lack of evidence on tariff effectiveness at reducing trade imbalances, the risks of retaliation and potential deterioration of economic growth suggest policy 3 may be more harmful than good. Instead, improving infrastructure will likely not invoke reductions in employment and equality, nor will it deteriorate relations with china, making it economically and politically superior. Whilst policy 1 may incentivise exports, policy 2 achieves this by providing capacity and speed whilst enabling the establishment of new industries and opportunities that benefit the entire economy.

Promoting exports through tax credits experiences similar issues to the government’s currently implemented ‘Exporting is GREAT’ campaign which is limited by business owners lacking skills and contacts, and a lack of awareness and access of support for entering into international markets (Downes et al., 2018) suggesting the policy may minimally impact the trade imbalance.

Sources:

- Barnett, J. (2022). CPS: Shield exports from tax to boost Global Britain and small business

- Barns-Graham, W. (2022). UK trade deficit with China triples prompting fears of becoming ‘heavily dependent’ on Chinese goods. Institute of Export and International Trade..

- Bivens, J. (2017). The potential macroeconomic benefits from increasing infrastructure investment. Economic Policy Institute.

- Department for Business, Innovation & Skills (BIS). (2011). International trade and investment – The Economic Rationale for Government Support. Economics Paper no. 13, May. London: BIS.

- Donnarumma, H. (2022). UK trade with China: 2021. Office for National Statistics.

- Downes, R., Kleinman, M., Wilkinson, B. & Hesketh, R. (2018). Delivering economic growth through exports. The Policy Institute at King’s. Kings College London.

- European Commission. (2010). Internationalisation of European SMEs. Brussels: Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry, European Commission.

- Furceri, D., Hannan, S.A., Ostry, J.D. & Rose, A.K. (2018). Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs. NBER Working Papers 25402, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Furceri, D., Hannan, S.A., Ostry, J.D. & Rose, A.K. (2020). Are tariffs bad for growth? Yes, say five decades of data from 150 countries. J Policy Model. 42(4):850-859

- Harris, R. & Li, Q. C. (2007). Learning-by-Exporting? Firm-Level Evidence for UK Manufacturing and Services Sectors. Working Papers 2007_22, Business School - Economics, University of Glasgow.

- Hayes, A. (2022). Trade Deficit: Advantages and Disadvantages. Investopedia.

- Horsman, E. (2020). How can infrastructure improve competitiveness? National Infrastructure Commission

- Hourston, P. (2022). Cost of living crisis. Institute for Government.

- Lawrence, F. & Myers, A. (2023). Trade and Investment Factsheets. Department for Business & Trade.

- Mace Media Line. (2022). Global Britain Commission call for new focus on infrastructure in trade policy

- Msulwa, R. (2021). What is the role of infrastructure in relation to levelling up? Bennett Institute for Public Policy. University of Cambridge.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2022). Balance of Payments, UK: April to June 2022

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023). Public sector finances, UK: January 2023

- Pisu, M., Pels, B., & Bottini, N. (2015). Improving infrastructure in the United Kingdom. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1244, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Reynolds, M. (2022). Investment in infrastructure is central to unlocking the growth the UK needs. Mace.

- York, E. (2022). Tracking the Economic Impact of U.S. Tariffs and Retaliatory Actions. Tax Foundation.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Gaby Stokes

Date: 19 March 2023

RE: Uyghur Muslims forced Labour in Xinjiang

Summary

I am requesting for there to be a complete ban on trade of polysilicon goods. The production has used forced labour by Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang exploiting modern day slavery act.

To ensure the UK still has the capacity to import Polysilicon from China, the government should subsidise its ethical production in alternatives to Xinjiang factories. The policy analysis develops off current work in US and other recommendations.

Background

Xinjiang is populated with around 10 million Uyghur Muslims (Gries, 2023). As a part of the CCP’s attempt to grow loyalty of religious minorities to the party, socio- economic conflict has arisen leading it to be ‘one of the most heavily policed regions in the world’ (Zenz, 2019 Cited in Kriebitz & Max, 2020). Under Xi Jinping’s administration ‘re-education camps’ of Uyghur Muslims have been discovered.

UK MP’s have declared this CCP policy as an act of genocide against the Uyghur Muslims through the acts of forced assimilation and labour acting as a crime against humanity (MPs, 2021). According to the UN (2022), evidence from a 26-person interview found ‘patterns of inhuman, and degrading treatment in the camps’ between 2017 and 2019 (Maizland, 2022) going against Article 23 Declaration of Human Rights that states free choice of employment for citizens (Murphy & Elima, 2021).

This impacts the UK as forced labour being connected to the western supply chain and considering China being UK’s largest importing partner as of 2021, contradicts the UK’s moral stance on forced labour (Office for National statistics, 2022). We need to make sure that the UK is not contributing to the abuse in these factories in Xinjiang, and so a new UK policy is needed to try and prevent this ‘genocide’ through acts of modern slavery.

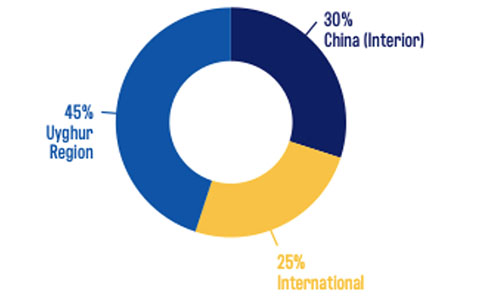

Xinjiang factories are responsible for forced labour in many industries, but since China is the world’s largest producer of solar grade polysilicon, which are used to make solar panels, it’s vital that the UK maintains Polysilicon trade relations via ethical sources (Figure 1).

Since 4/6 of Polysilicon producers are in the Xinjiang region, efforts are needed to shift production away from forced labour camps (Ambrose and Jolly, 2021). Investigations have found that 40% of UK solar farms are built from leading Chinese companies including Trina Solar so new policy needs to shift this pattern of production (Ambrose and Jolly, 2021).

Analysis of policy options

Recognising the crime of humanity polysilicon factories in Xinjiang have brought I propose these following recommendations:

1. ‘Solar companies listed in this memo should conduct in-depth human rights due diligence on its factory labour, including audits and inspections. This should include an assessment of the conditions and safety of workers using a range of information’. (Gries, 2023):

Such Solar Panels companies have been using Polysilicon since 2016 including, Bluefield Solar and Foresight Solar. According to a 2020 Report by The Foresight Solar fund, Xianjiang region companies including Solar Trina had supplied 13% of its panels to UK sites. (Ambrose and Jolly, 2021). This shows the entire of the solar panel supply chain is a part of the human right exploitation. So, bottom-up investigations can be conducted into the ethical nature of polysilicon production.

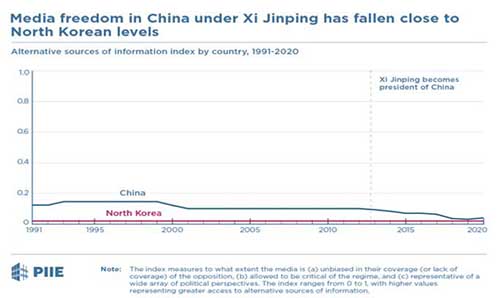

From this, new contracts can be rewarded to those who source from factories that respect human rights of religious minority (Ambrose and Jolly, 2021). Problem is that 3rd party audits may lack transparency while they may be rejected by President Xi Jinping. China’s index of media freedom has fallen to North Korea rate since his ruling, (figure 2). All solar companies should presume, unless evidence, that production is under forced labour.

2. A ban on the importation of Polysilicon produced in factories located in Xinjiang region:

This would entail a large-scale restriction on any goods entering the UK containing the material. Large fines can be implemented on any companies found to be exporting goods to the UK containing Polysilicon under disguised names. This policy has the potential for a high success rate, with the US ban on cotton and tomatoes produced in the Xinjiang region effectively reducing the trade of cotton between the US and China by 41% between 2021 and 2022 (Taplin, 2022; Cockayne, 2022).

The efficacy of the USA’s policy demonstrates the potential for a successful ban on the importation of targeted products by sector produced in Xinjiang – with the UK ensuring they are not engaging with trading partners actively breaking universal human rights. This will help the UK separation from the acts of Coerced Labour. But, regional import ban may result in reallocation of production of polysilicon under forced labour to other regions of China so not fixing the ground problem.

3. Subsidise Chinese companies that manufacture polysilicon in factories not located in the Xinjiang region:

The use of sanctions has not been an effective measure against slave labour conditions – the responsibility lies on Western buyers to find ‘slavery free’ goods, which are often more expensive as labour wages for workers are higher. Cockayne (2022) states that moving production away from factories located in Xinjiang would be at a cost of USD $500 million.

If the British government helped subsidise companies through this transition, the price of ethically sourced Polysilicon would be lower for UK consumers and encourage faster emergence of alternative supplies. But this is not an immediate change and so will not help Uyghur Muslims in the short run.

Policy recommendation

The most feasible policy I put forward for the UK to intervene with this human right abuse issue is Policy 2 due to past evidence of import bans being successful for the US. With, UK and USA having similar imports patterns and economic models it increases the probability of it working for UK.

To increase this further you could tie this policy with other countries such as South Korea who rely on polysilicon as it more likely to succeed if backed up by more than 1 country. So collectively, a reduction in trade means there will be less pressure on China’s export – orientated economy to source cheap, unregulated labour.

The outcome of this will relive Uyghur Muslims from being a target of this type of Western demanded labour, protecting their human rights.

Sources:

- Ambrose, J. and Jolly, J. (2021). Revealed: UK solar projects using panels from firms linked to Xinjiang forced labour. The Guardian.

- Cockayne, J. (2022). Making Xinjiang sanctions work. University of Nottingham.

- Gries, P. (2023), Module 3: Trade and Investment- What are the promises and perils of China’s economic reach?, Global Trade – How do Chinese exports impact foreign consumers and workers. Available at: Manchester University.

- Gries, P. (2023), March, Module 7: Population, Ethnic Minorities. Is China a Land of ‘ethnic harmony’? Available at: Manchester University.

- Hendrix, C.S. (2021). Third-party auditing won’t solve US solar industry’s Xinjiang problem | PIIE. [Accessed 21 Mar. 2023].

- Kriebitz, A., Max, R. The Xinjiang Case and Its Implications from a Business Ethics Perspective.Hum Rights Rev 21, 243–265 (2020)

- Lehr, A.K. and Beckrakis, M. (2019). Connecting the Dots in Xinjiang: Forced Labour, Forced Assimilation, and Western Supply Chains. CSIS Human Rights Initiative, pp.1–30. Available at: 202-887-0200 [Accessed 19 Mar. 2023].

- Maizland, L. (2022). China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Council on Foreign Relations.

- MPs (2021). The UK’s responsibility to act on atrocities in Xinjiang. houseofcommons.shorthandstories.com. [Accessed 20 Mar. 2023].

- Murphy, L.T. and Elima, N. (2021). In Broad Day Light: Uyghur Forced Labour and Global Solar Supply Chains. Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice.

- Office for National Statistics (2022). UK trade with China: 2021 - Office for National Statistics

- Xiuzhong Xu, V., Cave, D., Leibold, J., Munro, K. and Ruser, N. (2020). Uyghurs for sale: ‘re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang. International Cyber policy Centre, 26, pp.03-41.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Joe Hindley, University of Manchester

Date: 20 March 2023

Re: Increasing UK aid investment in local institutions in developing nations to allow for more effective management of Chinese investment

Summary

Chinese foreign investment has increased dramatically in recent years, with outbound direct investment growing from next to nothing at the start of the millennium to $100 billion in 2015, making China the world’s third largest foreign investor (Lee, 2018). A substantial proportion of this investment is targeted at developing countries - particularly in Africa - with loans for transport, communications and energy being a priority.

However, often little regard is given to the ability for the recipient country to repay these loans, causing countries such as Ecuador, Zambia, and Sri Lanka to accrue large debts; often in return for poor quality or ill-conceived infrastructure projects (Dube & Steinhauser, 2023).

This is a call for UK policy makers to put a greater emphasis on investment in local institutions within countries targeted by Chinese investment to ensure they can efficiently manage these investments and reap the maximum benefits from such projects.

Background

China has been the premier investor in Africa since the advent of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 which has resulted in a trillion dollars in international loans. Chinese state-owned enterprises make up the largest proportion of investment inflow to Africa which has had several tangible benefits including income rises, increased trade and stimulation of the industrial economy (Yu, 2021).

Chinese construction companies can arrange convenient financial packages from Chinese banks and insurers, giving these companies an advantage in project bids (Dube & Steinhauser, 2023) . However, these companies and banks, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), often do not implement social safeguards or ensure that the recipient will be able to repay loans.

Additionally, many of the Chinese financed projects such as the $2.7 billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant in Ecuador and the Neelum-Jhelum hydroelectric plant in Pakistan have proven to be poor quality, with the latter permanently closing just four years after opening costing Pakistan $35 million per month in higher power costs (Yousafzai, 2022).

Further projects, such as road building in Zambia, have been called wasteful, saddling countries with huge debts for largely useless projects (Lee, 2018) leading some, such as Tanzania’s president, to label such investments ‘exploitative’ (Chaudhury, 2019).

While Chinese investment certainly brings huge benefits to the developing world, mismanaged projects and exploitative loans also have the potential to do more harm than good, costing recipient countries hugely.

Policy options

UK to provide investment alternatives to China:

Africa and the rest of the developing world present a massive investment opportunity to all countries looking to vent domestic capital. The UK government could adapt its investment strategy to out-compete China by making competitive loan offers on infrastructure projects of the highest quality and are well thought through. This would ensure the recipient nation gets a fair deal and that projects are effective, while also benefiting the UK’s economy.

However, it would be an unfeasible undertaking for the UK to match the foreign investments of an economy five and a half times its size - not to mention the incredible advantage that China has over the UK in terms of domestic manufacturing, meaning the UK would also have to overcome China’s advantage in material and labour supply. Moreover, China maintains an advantage in investments over the UK through its policy of not imposing any political conditions (with the exception of adoption of the ‘one China policy’) on recipient countries (Information Office of the State Council, 2014).

This makes China’s loans more attractive to developing nations as the no strings attached approach means the projects are often completely on the recipients’ terms - something the UK government would be unwilling to support in cases where human rights or democracy are at risk. Thus, whilst this policy option may have some benefits both for the UK and developing nations, it is not scalable, would require an entirely new national investment strategy and is very expensive.

Working with China:

Working in partnership with China to provide equitable loans and investments is another policy option. The UK could offer additional financing and expertise for projects on the premise that only well conceived, mutually beneficial projects are undertaken.

However, Beijing tends to work unilaterally on aid projects and investments and would be unlikely to welcome UK intervention. Even if a partnership were accepted on certain projects, exploitative practices would continue in investments outside the partnership.

Additionally, the decoupling of China from western economies, and increasing tensions between China and the UK on the international stage also makes this intervention increasingly unfeasible.

Investment in local institutions to manage Chinese investments more efficiently:]

A third policy option is to channel UK aid spending to strengthen the capacity of local institutions and confer expertise in financial, environmental, and labour assessments to local and national governments as recommended by Tjønneland(2020) and Parton (2020).

This policy option would ensure that the immense potential benefits of Chinese investment in the developing world continue to be realised, whilst empowering the nations themselves to ensure loans and initiatives are well thought through, unexploitative and will not lead to the build up of unnecessary debts.

This intervention would help to ensure the vast swathes of Chinese investment is spent responsibly on effective projects, saving the recipient country millions of dollars in interest repayments and repairs of low quality construction projects.

However, this intervention could be seen by the CCP as meddling in their foreign affairs and would certainly aggravate Chinese companies looking to profit from investments in projects which could increase tensions between London and Beijing (Parton, 2020).

Status quo:

By not acting, the UK government runs no risk of upsetting the CCP in a time of escalating tensions between China and the West. However, by doing nothing, exploitative loan practices will continue, costing developing nations millions of dollars annually, potentially undoing the work of UK aid investments.

Policy Recommendation

From this assessment, investment in institutions to empower local and national governments to make well informed decisions in the face of seemingly limitless Chinese investment is the best policy option, ensuring developing nations reap the benefits of effective Chinese investments and avoid wasteful projects.

This option will guarantee that local and national governments vulnerable to so-called debt-traps make well informed decisions with adequate long term scope for the investments. It also offers excellent value for money for the UK government as the relatively cheap intervention has the potential to save developing countries, such as Pakistan, millions of dollars annually, aiding their development.

Sources:

- Chaudhury, D. R. (2019). Tanzania President terms China's BRI port project exploitative. The Economic Times.

- Dube, R., & Steinhauser, G. (2023, January 20). China’s Global Mega-Projects Are Falling Apart. The Wall Street Journal.

- Information Office of the State Council. (2014). China’s Foreign Aid. Beijing.

- Lee, C. K. (2018). The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa. University of Chicago Press.

- Parton, C. (2020). Towards a UK strategy and policies for relations with China. The Policy Institute, King's College London.

- Saeedy, A., & Wen, P. (2022, July 13). Sri Lanka's Debt Crisis Tests China's Role as Financier to Poor Countries. The Wall Street Journal.

- Tjønneland, E. (2020). The changing role of Chinese development aid (CMI Insight 2020:1) 8 p. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Yousafzai, F. (2022, November 23). Closure of Neelum-Jhelum project costing Rs10 billion extra per month to consumers. Retrieved from The National.

- Yu, S. Z. (2021, April 2). Why substantial Chinese FDI is flowing into Africa. Retrieved from LSE.

To: James Cleverly, UK Foreign Secretary

From: Ka Lok Chau, Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)

Date: 21 October 2023

Re: Issues involving the National Security Law in Hong Kong

Summary

The National Security Law (NSL) 2020, passed by the Chinese National People’s Congress, criminalised secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign or external forces. The vaguely defined law uses the pretext of national security to “‘decimate’ the territory’s freedoms” and peaceful protests(Hong Kong security law has decimated freedoms, 2021).

The UK must confront this issue as it bypasses HK’s Basic Law which was established by the Joint Declaration between China and the UK. Strengthening Sino-UK communication can encourage a diplomatic solution and calm the CCP’s fear of separatism in HK. UK mediation and negotiations would be dependent on the willingness of China to participate in the global economy and geopolitics or risk being further ostracised by the international community.

Background

The UK’s commitment to Hong Kong dates back to the mid-19th century Opium Wars and the ensuing colonisation of the coastal region. Its post-colonial economic and political importance led to peaceful cooperation for its transfer back to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The culmination of maintaining positive relations allowed the negotiation of The Joint Declaration in 1984, which stipulated the “One Country, Two Systems” scheme of rule and ownership.

While the British conceded ownership, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) would receive a “high degree of autonomy” and civil liberties for 50 years, with Britain maintaining the right to “monitor its implementation closely.” (House of Commons Library, 2021)

Observance of this treaty is a duty of the UK parliament and violations of this justify political intervention in Hong Kong. Therefore, Beijing’s controversial NSL demands attention and a change in foreign policies. The ambiguously defined NSL has criminalised many freedoms previously enjoyed by the HK public under Basic Law and symbolises a breakdown of the democratic process.

Its effects are perfectly demonstrated by the high-profile arrest of Jimmy Lai, the owner of a pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily, under “charges of conspiracy to publish seditious material and collusion with foreign powers” who will be trialled by non-impartial judges(Yu, 2022).

The law challenges the freedom of expression and has been used to prosecute protestors outside of the standard judiciary system. Additionally, The International Association of Lawyers, a non-governmental organisation, has already questioned China’s violations of Basic Law, highlighting several concerns including “the designation of a list of judges to hear NSL cases by the Hong Kong Chief Executive” (UIA, 2020).

Policy Options

Current foreign policies have implemented alternative citizenship pathways for Hong Kongers, however, it neglects to directly confront Chinese obstruction to HK’s autonomy. The launch of the British National (Overseas) visa in 2021 allowed the option for permanent settlement into Britain and be protected by British national laws. While this offers shelter for HK citizens, it fails to protect people who are unable to move or are already arrested under the new NSL.

Furthermore, it has already deteriorated UK-China relations with the People’s Daily article arguing that it violates the Joint Declaration and “seriously interfere[s]” in China’s domestic policies (Cai & Lian, 2023). The Beijing opinion labels protestors as advocates of independence, therefore, UK support furthers the breakdown of Sino-UK communication.

Another policy from the UK home office has been to denounce the growing authoritarian rule under Xi Jinping. Rishi Sunak, in a 2022 foreign policy speech, describes China as a “systemic challenge to our values and interests” but refuses to label it as a “threat” (Allegretti, 2022). Unfortunately, this has garnered a variety of criticism from Xi’s China as well as pro-democracy figures in Hong Kong.

Mainland China maintains that the West has “sugarcoated anti-China forces in Hong Kong as ‘fighters for freedom’”, further rejecting Sino-Western diplomatic negotiations (Zhong & Liang, 2023). Meanwhile, anti-Chinese spokespeople characterise UK foreign policy with a lack of action and failure to recognise the security implications beyond economic concerns (Duggan, 2023).

Continuing these policies will further worsen UK-China relations while neglecting meaningful change to Hong Kong under the NSL. Due to this lack of escalation, the UK has successfully averted economic sanctions from China. Significantly, its implication would be drastic as China, by 2021, became Britain’s “largest import partner” alongside a £39.1bn trade deficit (Donnarumma, 2022). Consequently, British political influence over China has suffered from an increased interconnection of economies.

This would also indicate that any foreign policy based on aggressive trade sanctions, similar to the US trade-war approach, would become unfavourable for the UK economy. Despite this, a hard-line approach could solidify the UK’s power in global geo-political, pro-democracy discussions.

In contrast, UK-led negotiations can confront China’s gradual dismantlement of the political system, which has led to HK’s movement from a “flawed democracy” to a “hybrid regime” in the Economist’s 2020 Democratic Index. Its analysis also highlighted that the NSL “curtails Hong Kong’s political freedoms and undermines its judicial independence” (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020).

However, it would be key to maintain the fact that these discussions do not promote separatism, but a reunification with democratic processes as stipulated by the 1984 Joint Declaration so that it does not provoke Chinese anger.

In addition, the release of political prisoners prosecuted by the NSL, including Jimmy Lai, is of paramount importance. It would be advantageous for Xi to cooperate and prevent further condemnation from global political bodies. Therefore, joining anti-China international bodies can be used as a threat to further alienate the PRC and force concessions.

Policy Recommendation

The need to restore HK’s civil and political liberties whilst maintaining a positive Sino-UK trade relationship requires constructive diplomatic communication. Current policies such as BNO visas and denunciation of Xi’s authoritarian regime jeopardise the possibility of a peaceful resolution.

Highlighted by the “wolf warrior diplomacy” tactic that encouraged a clash between Chinese consulate staff and HK protesters, on October 16 2022 in Manchester. Escalations of this policy could further anger Chinese nationalists, which the CCP relies heavily upon for its legitimacy (McAndrews, 2022). The danger of economic repercussions from China without a settlement of the issues brought about by the NSL would be catastrophic.

The policy for negotiation has the potential to anger pro-independence advocates, however, it would initiate negotiations for the re-establishment of freedoms and autonomy in HK. The UK should appeal to Xi’s desire for “One Country” without tarnishing its reputation of international economic cooperation. Simultaneously, it could strengthen UK-China cooperation and consolidate the UK’s influence in pro-democratic world affairs.

Sources:

- Allegretti, A. (2022). Rishi Sunak signals end of 'golden era' of relations between Britain and China. The Guardian. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Amnesty International. (2021). Hong Kong security law has decimated freedoms. Al Jazeera. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Cai, H. and Liang, J. (2023). UK should stop using BN(O) issue to interfere in China's affairs: Chinese authorities. People's Daily Online. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Donnarumma, H. (2022). UK trade with China 2021. Office for National Statistics (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Duggan, J. (2023). Hong Kong activists living in UK criticise Rishi Sunak for failing to label China a threat. Inews. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2020). Democracy Index 2020: In sickness and in health?. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- House of Commons Library. (2021). Hong Kong: the Joint Declaration. [Accessed 22 Mar. 2023].

- McAndrews, E. (2022). The Hidden Audience of China's Undiplomatic Diplomacy. The Diplomat. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- UIA. (2020). Hong Kong National Security Law Threatens Rule of Law. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

- Yu, Verna. (2022). China v Jimmy Lai: A tycoon, a trial, and the erosion of Hong Kong’s rule of law. The Guardian. (Accessed: 22 March 2023).

- Zhong, W., & Liang, J. (2023). West should immediately stop interfering in political manipulation of HK's judicial proceedings: Chinese FM commissioner. People's Daily Online. (Accessed 22 Mar. 2023).

To: Secretary of State, The Rt Hon. James Cleverly MP

From: Leonardo Parker, FCDO, London

Date: 9 March 2023

Re: United Kingdom trade and investment relations with the People’s Republic of China

Summary

The challenge presented by the rise of China is one of balance. Balance between our legitimate security concerns (which are shared by many of our allies) and the significant potential for economic benefit that comes with improved diplomatic relations. Our security concerns and foreign policy objectives can be addressed whilst also welcoming investment from, and trade with the PRC.

UK-China relations should not be viewed as a zero-sum game. We must recognise that not all Chinese investment is a threat; there should not be an assumption in place that suggests the motives for all investments are malign in seeking to undermine UK security interests.

The FCDO should advocate a more tailored and specific approach that seeks to maximise economic potential whilst maintaining sovereignty and security over sensitive industries and sectors.

Background

In the four quarters to the end of Q3 2022 China was the UK’s fourth largest trading partner accounting for 6.3% of total UK trade. Over the same period the value of imports from China exceeded the value of exports to China by £40.1bn (Department for International Trade, 2023). Whilst the notion of ‘reliance’ can be used as political hyperbole in favour of a certain cause, we should be looking for means by which we can strengthen our position.

The model of Chinese state capitalism makes the public-private distinction much more difficult than when dealing with liberal democracies and their free-market economies. It is often all too easy to trace the links from a supposedly private and independent company back to the Chinese Communist Party. This stems from the historical context whereby capital accumulation was accepted as part of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ provided it served the good of the nation and not just the individual.

The authority of Western governments to rule comes from their democratic mandates and whilst this is not true in China it would be a severe mistake to suggest that the rule of the CCP is any less legitimate as a result. The authority of China’s leaders comes not from the ballot box but from their ability to deliver on behalf of the population, we should therefore not fall foul to western projectionism.

Given this, the Chinese government has just as much of an incentive to foster a well performing economy as democratic nations do, but there is less of a requirement for the government to protect the rights of the individual. The policy recommendations that follow are cognisant of this information.

Policy Options

There are three broad strategies that could be taken by any British government: